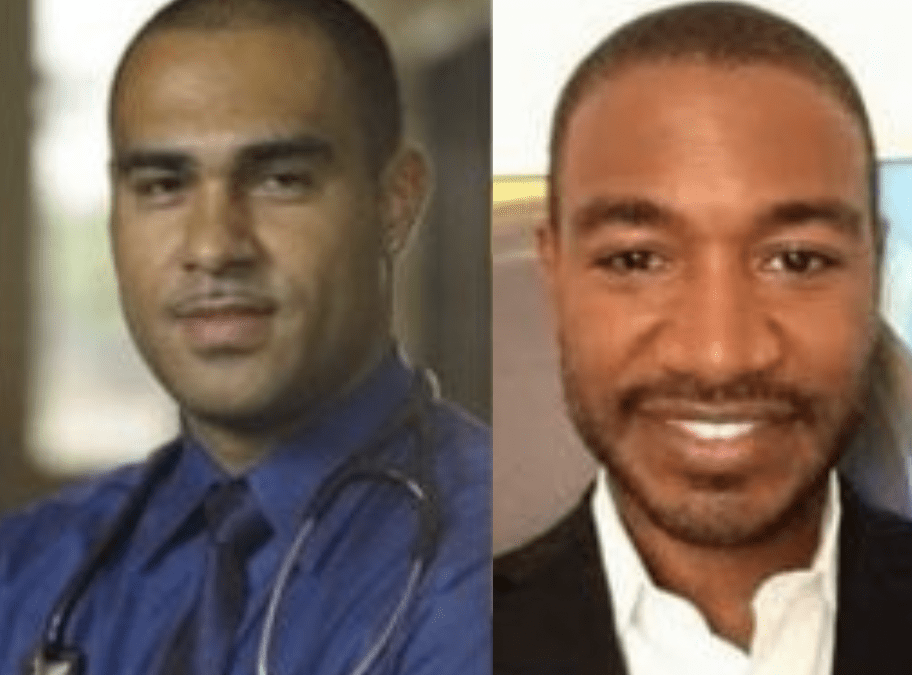

This fall, CCHE’s Dr. John Schneider and Katie Berringer sat down with Dr. David Malebranche, Primary Care Physician at the University of Pennsylvania Student Health Services, and Kali Lindsey, Deputy Director of amfAR, just after the AIDS Foundation of Chicago conference, Sex in the City II: Men, Sex, Love & HIV on September 25, 2014.

Grabbing a comfortable spot on a nearby park bench on a sunny, unseasonably warm day in Chicago, we launched into a conversation about David and Kali’s families, unexpected career turns, intersectionality, bisexuality, gay marriage, and what ignites their passion to do this work.

We started out by asking David and Kali to tell us a little bit about their backgrounds and their childhoods, and what initially motivated them to enter the field of HIV service, research, and policy.

David Malebranche: I’ve only been to Haiti once, actually. My dad emigrated from Haiti in the sixties and he was actually a surgeon so he met my mom while he was completing his training in upstate New York and she was in nursing school, so they had a medical background already. I think where it comes into play is the expectations, you know… I also remember as a teenager when the HIV epidemic hit. I was in college and I was working as a janitor in upstate New York in a hospital and the head of the whole staff got us together and they were talking about this new virus and how to be careful with folks. Back then they were talking about the four H’s: Hemophiliacs, Homosexuals, Heroin users, and Haitians. And they weren’t saying just people who emigrated from Haiti, they were like, if you’re of Haitian descent. And so I remember, I was like, I’m fucked because I’ve got two out of four! Like, what the fuck. And I remember that crossing my mind, because I was like 19 at the time. I was like, okay… But that was the first time I had heard about it.

Then, as I started to get more sexually active at a time when there wasn’t HIV testing… I missed Baby Boomers by four or five years and so I was in Generation X and we didn’t really—I didn’t really experience a lot of people dying around me, no personal friends. But I did experience people testing positive. It would be like in one week I would get calls from three or four friends about them testing positive and then nothing would happen for months and then all of a sudden there would be another wave of three or four people testing positive.

So, yeah, I got involved in medicine from my dad and his influence. Although, he was a surgeon and I didn’t want to be a surgeon. I think in medical school there were a lot of sick people. I was in medical school from ’91 to ’96 and they didn’t have too many medications back then. It was before AZT, so I watched a lot of people die. I consoled a lot of people who died. I pushed morphine on a lot of people who died. And, um, that kind of had an impact on me to get involved. And I also saw a lot about how people living with HIV got treated, which got on my last fucking nerve. Medical staff would cut their eyes on them, looking at them like they were lepers. You know it was just bullshit and I kept thinking, you know, I can do this better than they can. That’s how I ended up getting interested in it from that perspective.

John Schneider: So, you know, in terms of Haitian black vs. African American, I mean, Great Migration sort of issues… How do you fit into that? As the son of a Haitian surgeon. That sounds pretty…

David Malebranche: Yeah, you know what’s interesting is that my mother is white and she’s from a humble background, so they put a flip on it where my father’s black but he’s from Haiti. People don’t want to acknowledge it, but Haiti being the first black republic to overthrow the French and how the slaves revolted in 1802… Coming out of that culture, you can’t help but have a certain pride in your heritage. So it’s not all earthquakes and HIV as the media wants to present. My father came to this country very clear that he was as good if not better than anybody he came across and he only started to experience racism once he got here.

Now, if you ask me about African American vs. Haitian… My father and I went through a lot of different machinations with that. We used to have these arguments about Caribbean vs. African American and he embraced what a lot of immigrants, both black and non-black, embrace when they come to the United States: that being black is less than, that black people are lazy, etc. So I remember him trying to indoctrinate me with that even as I went to school at Princeton. I went to a good school, and he was like, well you don’t need to just hang out with black people all the time. And I was like, um, dad these are black people at Princeton! Like, what are you telling me? And his whole idea was, if you want to do stuff for the black community you have to get in the cradle of white power structures in order to effect change. You know, being able to implement things, not just to pontificate about them. But over time I think as he lived in the United States, he’d say, “I’m black, I’m Haitian.” He’d say, “I’m a black Haitian”—they’re intersectional… Just like someone who’s a black Cuban they’re not just black or Hispanic… you’re black and Dominican, you’re both. But people can choose to be one or the other based on the privilege it will afford you.

But my dad was a trendsetter. He was the only black surgeon in upstate New York, in Schenectady. He became the chief surgeon. English wasn’t his first language—he still has a hardcore accent. To this day, sometimes I can’t understand what the fuck he’s saying [laughs]. But that kind of teaching, you know, taught me a lot. And the reason I say that it kind of comes full circle is because, when I was hitting my wall with academia and I had been at Emory for 11 years and I asked for a sabbatical, I had been writing a book for four years about different stories about my dad. And uh, they wouldn’t grant me my sabbatical, my chairman wouldn’t grant me my sabbatical. I’d just gotten promoted to Associate Professor and they were not going to give me sabbatical, which I thought was bullshit, and I’d just suffered a herniated disc and needed surgery on my back, which let me know I was taking on too much and I was like, why the fuck am I killing myself for Emory University? So I bounced. And I took a job at Penn with Student Health, which is something I was always interested in doing, but it was more 9 to 5. So—and this is where the Haitian resiliency comes in—someone tells me I can’t do something, to block me from something I need to do, I’m going to find a way around it. And I have been working in student health ever since. I worked on the book and when I’m going home to see my parents, they have actually a copy of the book and the first three chapters are about him and my mom and how they met and they’re going to give me their feedback and their suggestions and then it’s going to go to a copy editor for a second reviewing and I’m self-publishing it in March or April. And it has nothing to do with HIV or medicine, basically what it’s about is a narrative about a father and a son. And particularly a black father and a black son where it’s not… I’m celebrating him. I’m not saying I made it in spite of him, or despite the fact that he wasn’t there, I made it because he was there. And there aren’t that many stories that celebrate black fathers. They’re out there, but they aren’t told that often. And I wanted to share that story. So it will be interesting. I’m interested to hear what my mother and him think this weekend.

John Schneider: That’s awesome. Good for you.

David Malebranche: Yeah, also my mother had a tough time growing up. She was kind of the Cinderella of her family. Everybody kind of dumped on her and she did the work around the house. And I think that’s why she calls out racism more than my dad does. She’s like, “That’s messed up. That’s racist.” And my dad will be like, “Donna, calm down” [laughs]. And he calms her down, but she’s all over it! He’s like, “That’s not racist.” And so it’s interesting… being oppressed. And when you have that experience and you understand what being oppressed means, and being underappreciated, and being dumped on. You can feel—it doesn’t matter what race you are—you can see if there’s a class of people—in the United States it’s class and race. So if you see that in the United States, it’s black people, you’re going to empathize with that, and I think my mother she understands that, she gets that.

Katie Berringer: So, Kali, what about your story?

Kali Lindsey: A decade later—and, yes, I am a decade younger!

David Malebranche: You know what! [laughs]

Katie Berringer: Well he deserves that after all of his comments about “Baby Boomers” at his talk!

Kali Lindsey: I don’t know, I see my experience as having a lot of parallels to David’s. You know, it’s really about locking into sources of resiliency. Recognizing where you have potential to go against the grain and taking those opportunities and teaching yourself how to overcome challenges. You know, unlike David, I didn’t come from an immigrant background, I came from a family that came from the slave trade and so I don’t know all about my history or origins. I know essentially what’s available from whatever documents my family was able to obtain from the National Archives. So, while I can get my DNA analyzed, I am basically ignorant of what my ancestral roots and cultural history were. This has left me to rely on my “American culture” but that creates challenges for many of us who experienced growing up as a black person in this country. This recognition, I felt, gave me permission to kind of write my own story. And in many ways, that is how I lived my life because my parents and most of my family draw their resilience from their religion, but the church was also a source of trauma for me, as it is for many others who are same-sex attracted. I don’t know any gay people other than myself in my immediate or extended family. So when I started experiencing my same-sex attraction—it wasn’t really a gay identity because I didn’t have access to that at that point—I was kind of forced to figure everything out on my own.

And, at some point, I recognized that I had been impacted by several things that I had experienced living and growing up in Detroit during the era of Coleman Young. These formed some of my earliest impressions of being a black man in the U.S. At the time, when he was confronting stubborn crime and the white-flight from the city following the riots in the 1970s, many believed he hated white people. For many black people in the city, his efforts were more about encouraging leadership and accountability among Detroiters, including those who were black or white, to stand up for themselves and their community and not have outsiders dictate their priorities for them. It was transformative in a way because it was also very empowering for me to come in and look at images of powerful and successful black individuals asserting themselves and our individual and collective potential with such force —particularly those who were visible as civil rights were still elusive for many black people in the U.S. and remains that way for far too many. It served as a model to combat what some have called a “slave mentality”, where oppression, including poverty and discrimination, a police state in our dilapidated communities and the effects of incarceration, and school systems in disrepair stymie the best intentions to mobilize the community. That experience kind of helped me identify tools that I can employ to forge my own path, regardless of my own experiences with oppression.

You know, I think one of the things we get so wrong when we respond and think about things in the African American community is that we don’t think enough about families as central to health, we think about the black church. And I think that the black church is only what it is because of the mothers at the helm of it and because of the black families that comprise its membership—we can thrive without churches, they cannot thrive without families. It was because of my mother that I became a man who thought for himself and created his own path. It was my father that I prioritize my health and hold myself to a higher standard. Because, despite my grandfather not completing his education, he impressed upon my mother the value of education. He pushed her to go to undergrad, to get her master’s degree, and she became an educator. My dad had a different experience growing and decided not to complete college, yet they both taught me the value of hard work and persistence. The very ingredients I believe have led to my own success. You know, different individuals, with different backgrounds, really chose their own paths and achieved great things, at least in my opinion. If it was possible for them with less than what I have been given, then it was possible for me. As I always heard growing up, “to whom much is given, much is required” and I hope to use what I have been given to the best of my ability. This is what gave me the strength to relocate from Detroit. I started getting tired of the politics and the sadness and despair that you see in Detroit day in and day out, I started to think more broadly and to investigate other avenues to educate myself… When I was in undergrad, I worked at Best Buy of all places, and the work ethic that I had learned from my parents helped to earn me a promotion almost every three months. I started as a customer service rep, then I was a supervisor, and within a year, I was a manager. And eventually I graduated from college in April and they handed me the keys to a store. I was 21 and I had all of this responsibility.

At the same time, I was this incredibly healthy kid who nothing ever happened to and I started getting colds and became concerned. And I had heard enough about the “4 H’s,” this “gay epidemic,” but that was only something that happened to people who were unhealthy and I went to my pediatrician every year. There was all of this information that I thought would protect me from HIV but it crept right in while I wasn’t paying attention and I had to confront that. Confront that I had learned what HIV was, but not how to realistically protect myself from acquiring it. And that pissed me off, I had gone through health education, and the health care system, I had been tested in clinical systems before. But all this information about how I could protect myself missed me, or at least was not helpful enough to protect me. And when I talked to other people, they were misinformed as well. And then I got so angry about the fact that I got infected, in spite of all the opportunities {the different health professionals that I interacted with} to stop that infection that I started doing community work to help to address the problem, then got equally frustrated by the kind of {HIV prevention} work they were telling me to do in the community. They said, “Go out and talk about HIV prevention, but you can only talk about abstinence. You can talk about condoms, but tell them the only way to be safe from HIV is by practicing abstinence.” This was in 2003. It was the A,B,C. era: It was Abstinence, Be faithful, and use Condoms. And my question was, “So how does abstinence until marriage strategy work when LGBT people can’t be married? How does that actually play out in terms of the advice that you’re giving to individuals?” Of course, the implication was that sex should only occur between a man and a women and only if you are married. The response I got from my supervisor was, “These are the rules, you have to abide by them.” But the rules didn’t make any sense and they were harming people. And then essentially they sent me out and I was doing these testing programs on a biweekly basis for an organization that was for LGBT and at-risk youth, called the Ruth Ellis Center in Detroit. I was doing HIV testing and health education programs. And some participants would come back repeatedly, and ask for an HIV test. I would ask, “Why are you here?” And they would say, “You know, I got the information, thanks for the condoms, however, you know, my partner this… Or, this situation that…” Or, all of these intersectional issues preventing them from using the information, the tools that were provided to them.

So I was like, these programs, these policies need to change to reflect the actual experience of the people that we’re attempting to serve. And I started getting more and more involved, looking for more opportunities to have a bigger impact on the epidemic. I started getting involved with this organization called NAPWA [National Association of People With AIDS] and they had an event called AIDS Watch that was all about bringing these issues to Capitol Hill and advocating for better HIV programs and services. Similar to David’s Emory experience, my job did not support my interest in advocacy and wouldn’t allow me to attend AIDS Watch. Shortly after that, I decided Washington, D.C. is where I needed to be. I sold most of my things, packed what I could in my truck, told my parents I had a job (though I really didn’t have one at the time but wanted them to worry less), had a friend on the other side, slept on his couch for about three weeks, and fortunately got a job with the Human Rights Campaign immediately thereafter. As a result of that I started doing field political work, trying to get progressive candidates elected and met some individuals who were doing HIV advocacy, over the summer—actually, at a colleague of ours’ house, Ernest Hopkins—at an event that he was having during Black Pride Weekend in DC. I connected with some of NAPWA’s leadership at the time at the event. That is where my transition into national HIV advocacy began.

David Malebranche: [laughs] They made you an offer you couldn’t refuse?

Kali Lindsey: [laughs, nodding] They made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. So, six months after I started working at HRC I took this job with the National Association of People With AIDS doing programmatic work. But they kept hearing me talking, they kept hearing me push back against the system, and they said, “I think you need to do policy.” At the time I really didn’t have a full grasp of what public policy was and asked, “What’s policy?” and essentially got my answer on the job thereafter. I was working with a man by the name of Robert Greenwald, who works at the Harvard Law School in the Treatment Access Expansion project, and Frank Oldham who was the Executive Director of NAPWA, and they said, we want you to advocate on behalf of these core issues for People with HIV within these structures. And as I got deeper in, I got more and more interested, I got more visibility, and then literally the same thing that happened at Best Buy happened again. I started in NAPWA in programs and then was the Vice President of Public Policy in about a year and then I got offered a job in Atlanta doing social marketing and worked on the Testing Makes Us Stronger campaign among others. Got frustrated again because the CDC was calling all of the shots and I had grown accustomed to pushing back. So, the social marketing firm told me I had to toe the line and instead, I went back up to New York to do policy. Patrick McGovern, who we actually just saw at the AFC conference, brought me up to Harlem United, which is an FQHC in Harlem and that was when my whole world changed because I saw this broader environment of how healthcare delivery was actually being implemented in a community of individuals who suffered from all of the co-morbidities that place people at risk for HIV and all health disparities. A large portion of the patient population struggled with Axis II mental health conditions. Most of them had low socioeconomic status, many were homeless, many used or abused some kind of substance. Yet, the majority of them were coming to this healthcare clinic and were doing well. Ninety percent viral suppression, regular retention in their healthcare appointments, all of the staff knew them by name, and they would be there, they would support each other. And there was this little familial environment of everything that we try to do at the federal level and everything that I saw as necessary when I was working in Detroit was happening in Harlem. And I was like, all we need to do is make the policy work with the resources and we can actually do programs that matter and make a difference. Then the Affordable Care Act passed, Patrick took a job with Gilead, I left and came back to DC to continue the work, and I’ve been in DC since then.

Katie Berringer: Well, that kind of brings me to another, broader question I wanted to ask. Both of you spoke to intersectionality and structural risk. A lot of your research, David, really brings attention to these issues. And I loved the phrase that you used, Kali, for the need for policy that brings “intentionality to intersectionality.” So I guess I would love for you both to speak a bit more generally to how on the clinical level or the policy level we can identify and then address those structural risks—especially things that you talked about like structural violence and discrimination and trauma that don’t necessarily have clear cut policy implications or solutions.

David Malebranche: You know, I think the bad thing is that our medical system right now isn’t cut for it. I mean, it’s just not. It’s run by business people, it’s formulated on the business model. It’s even trickled into the public sector, where it’s all about levels of productivity and getting rewards and this system that’s crunched into where, you know, people can’t function and there’s a high tendency for burnout of providers. And the unfortunate thing, particularly when we talk about HIV is that this is not a McDonald’s, fast food, extra value meal thing that you’re doing here. You have to take your time with it. When I worked at Grady at the Pond’s clinic, a new visit was 45 minutes because they knew you needed the time to do a full physical exam and a full history and you were dealing with folks who had substance abuse, no insurance, homelessness, this, that, and the other. Where I work now at Penn, it’s 15 minutes. But you would think that a lot of these kids have insurance and they’re more privileged but when they come in there’s a lot of adolescent and early adult stuff that they’re going through—suicidality, mental health stuff, substance abuse, other kinds of things that their going through—and you have to take your time. I think the problem is that—something has to break at some point. You can’t dish out PrEP like it’s a vitamin and just say, “Okay we’ll see you in 6 months!” You just can’t do that right now. You need to follow people. And especially because of how fluid risk is and kind of what happens and being able to kind of understand it. You know, how do you administer PrEP to somebody who’s 19-years-old and is identifying initially as one gender, tests HIV positive at some point, and then transitions to a transwoman—and how do you provide hormones and this, that, and the other? Plus the person’s in school and then you’re trying to get her changed from PrEP to antiretroviral treatment? And they expect you when they’re scheduling these follow-ups for you to get through it in 15 minutes. And you have to go through your schedule and change it up. I think from a clinical perspective this will be interesting with PrEP. There are a lot of people who are doing interventions that focus on providers and educating providers, but it’s not just the providers, it’s the systems.

We did a study 10 years ago with black MSM where they were talking about how their interactions with all medical personnel influences the overall experience… Whoever the woman who’s at the reception desk sucks her teeth at you or rolls her eyes, or the phlebotomist who makes a comment—it’s not just the providers, they’re going through a system. And the more that medical systems are becoming fragmented like that or becoming multidisciplinary, the more different areas you have to do cultural competency, because by the time the person gets to see the doctor or the nurse practitioner or the PA, their blood pressure is through the roof because someone else has gotten on their nerves.

And, like it or not, HIV is becoming a manageable, chronic disease, and we’re going to have to start shifting focus… And it’s kind of an ironic thing, because the silver-lining of HIV is that it forced us to confront issues of diversity, sexual orientation, desire, and talk about sex in ways that we wouldn’t have if HIV hadn’t come on the scene. I don’t think the country would have taken this trajectory at all. The interesting part that’s going on now is this kind of flip, where now we have to kind of get out of crisis mode. We have this kind of expectancy shift, if you have an HIV diagnosis, from, “Oh, shit, I’m going to die in two or three years. Let me get my shit together” to “Oh shit, I can do everything now that I was supposed to do before, so now what do I do?” I think the job of providers is helping people through that transition—whether you’re a clinical provider, service provider, wherever you’re at. It’s not just about HIV. It’s about your whole health so how can we help you live a healthy life. HIV is a part of that, but you have all these other things you want to deal with. The problem is, how we spoke to it—and what I get frustrated with—funding streams enjoy crisis and pathology and they like moving backwards. That’s a systemic problem, that’s a cultural problem, that’s an institutional problem, that hopefully through policy and getting the right people in there and moving the agenda, we’ll get to a point where hopefully we’re conceptualizing health centers instead of illness models. Moving away from the deficit model and the illness model to more of a focus on how we can keep people healthy.

Kali Lindsey: The only thing I would say about that is—I mean, David kind of packaged it up with a nice pretty bow—but both when we think about how we invest in services and in organizations in our communities, I think we have to refocus on communities in our future work. You know, Richard Florida wrote a book on urban cities and how gay communities have, in part, really transformed US cities and brought a lot of people back from the suburbs and back into cities where they really want to have opportunities to connect and socialize and rebuild a tighter sense of community than can be difficult in the vastness of suburban living. I think in so many ways—kind of like the challenges many people have with “MSM” as a term—the challenge that I have with it is that not only is it not an identity but that it doesn’t attach you to anything. Just like most individuals’ risk tends to be derived from a broader social system, most often a community, their health behaviors are also manifestations of that community and the interactions that occur within it. Yet, we completely erase and make irrelevant that experience when you describe these men as “MSM.” You make irrelevant all of the experiences that factor into their cognition, their emotion, their motivation to engage in risk reduction behavior and to engage in the health system. Until we focus on the communities, until we look at our CBOs as sources of employment, it doesn’t make sense. We talk about these contextual issues, you tell someone you care about HIV prevention but then you send them back into poverty, into homelessness, low educational attainment, unemployment. It’s like, how do you expect someone to prioritize HIV when you have all these other forces contributing to their despair, discrimination, and lack of access. And then you have all these smiling faces saying, “I care about you and I care about HIV,” but then won’t give them a job. Not only won’t you give them a job but then you’ll cut back on food programs when you know I can’t get meals three times a day. My mom worked in Detroit public school system where some students who lived in poverty were able to eat, in part, because of the meals that are provided at schools. So when you start to consider contextual issues, you start to understand why people are performing worse or why they might not be achieving educational attainment because we’re only looking at what has happened to them, but leaving what has caused them to get there unaddressed. The same thing with diabetes: you don’t look at obesity and say, well it’s just the over-eating that’s a problem. You have to ask why they’re overeating. Is it depression, mental health? Is it lack of access to quality food, quality groceries so that you can make healthy meals and avoid the over-processed sugary foods? But we don’t look at the communities where people come from. We just say, you’re lazy and you’re fat and that’s why you’re obese and you’re sick and you’re a drain on the healthcare system. Until we re-focus on communities, we can’t really have intentionality about addressing the intersectionality.

David Malebranche: It’s interesting, when you said that I thought about Dr. Joe Marshall. He has an organization in the Bay Area called the Omega Boys Club [now Alive & Free]. He’s done presentations for probably over a decade or even longer talking about violence as an epidemic, as like a virus, and talking about it in communities. And he’s used the example of diabetes and said, when someone gets admitted in diabetic ketoacidosis, you get a diabetic teacher, you give them education, you do this, that, and the other. Some young person—and typically it’s a lot of young black males—comes in and gets shot, they do surgery, they patch them up, and they send them right back out. There’s no mental health counseling, there’s no consulting of a psychiatrist, there’s no evaluation of the community-level violence that they are having to deal with. You would never do that for another disease, and you would never do that without follow up, but we do that all the time with victims of the epidemic of violence. Those are the contexts in which people live, where we say, oh, we need to reach these people about PrEP and this, that, and the other, and I’m like, he’s got to worry about getting shot, he’s not justconcerned about HIV. And then if you talk about PrEP he may not have insurance and may not have the money to afford it – so who the fuck is going to pay for it? And, you know, I think all of us get caught in these silos where we’re like, HIV, HIV, HIV, HIV and we think it’s important. And, yeah, it’s important but our communities and patients are saying “let me give you my priority list.”

And I think the challenge to a lot of—not only medical providers but service providers, public health officials—is to get our heads out of our own asses to say, “Okay, wait a minute. That’s my priority. What’s their priority?” And work with them. And that’s what you have to do as a provider. As I provider I was taught—and I heard this from several different clinicians—if a patient comes in and they have several different complaints, and you’re not sure where to go, you may have 15-20 minutes… You ask the patient, “Okay, look, in order to make this a successful visit, what are the one or two things I can do for you now? I may not be able to help everything right now, but what’s really bothering you today that I might be able to do to make this visit successful?” And they’ll tell you, “My back pain, or, my toe is really bothering me, or this cough.” And you address that and say, “You know what, come back in a few days and we’ll deal with the rest.” I always thought that was a smart way to handle it because you can’t do everything—it’s physically impossible with the time constraints. But I like the premise of reflecting it back onto clients/consumers/patients. To say, “What do you want out of this? What do you need out of this? What can I help you with?” And to go from there, see what you can do. But the problem is exactly what Kali was saying. If it’s not based in HIV testing, or treatment, or PrEP, they come in and they’re like, ”Oh, I’m negative, but I’m still suicidal, I don’t have a place to live, and my mother’s in the hospital, and I have these two younger brothers who I’m now the father of…” It’s like, “Well, you’re HIV negative so therefore you’re not pathological, so basically we have no services for you.” So systemically it has to change where we’re able to provide those services or put money into those services so that people will have a net and it’s not based on, “Ooh, something bad happened to you, now we’re going to help you.” Let’s help you now so that something bad doesn’t happen to you. It’s just a different way to approach it.

Kali Lindsey: You know, really thinking about the community aspect of it, now I talk to my friends a lot about this dichotomy: As gay men often we get kicked out of our homes when we come out or we experience violence in our community because there’s no appreciation for gay culture. Then we turn to these communities—even the white gay communities—where there is our greatest source of respite but where there’s also our greatest risk. And so often in our lives, a lot of the time we are experiencing risk where we are seeking sanctuary and community,—oftentimes in those same circumstances. And I compare it to the Ferguson situation. Here it is, there are people of authority, systems of authority, and oftentimes the people we’re supposed to trust and oftentimes we’re confronted with someone who is supposed to be sworn to serve and protect—and yet they’re murdering us, they kill us. And yet we’re supposed to look back at these systems and respect them, look at them as a source of support or development, look at them as opportunities to address some of the structural challenges that we have—and they continue to betray us. And every betrayal amounts to further distrust and another barrier to engage youth in health-seeking behaviors. Forget about the fact that when the person with diabetes comes in we don’t send them out with a bag of snickers. The person with the gunshot wound—why do we have military tanks and individuals with guns strapped to them coming into communities when I’m already traumatized by gun violence? And now the individuals that are supposed to keep me safe are approaching me with machine guns, with guns drawn, and tear gas, and treating me like a criminal—where do I go for sanctuary? Every time I’m trying to interact with something that’s going to take me forward, I’m met with this incredible risk that it’s either going to impact my health or, worse, it kill me. So part of the issue is that we have to re-think some of the structures that we have in our community, because as long as we continue to be betrayed by these authorities and these systems of trust, we’re not going to be able to address these underlying issues.

Katie Berringer: Thank you so much. I think we probably have enough already, but I did have one other question for you. A lot of your research, David, has done so much to expose one particular way that we pathologize black male sexuality in the myth of the “down low” and the “bisexual bridge.” And then this question came up from the audience after your talk about the “silent B” in LGBT, and I think September 23rd was also National Bisexuality Awareness Day, so I thought it would be appropriate to ask you a question about bisexuality.

David Malebranche: I think it’s interesting because this LGBT thing… I’m a firm believer that transgender folks need their own space with that. Because our transgender brothers and sisters, to be honest with you, aren’t getting harassed as much from straight people as they are from gay and lesbian people who are uncomfortable with them. Like, the larger gay and lesbian community is horrible to our transgender brothers and sisters. And that’s kind of annoying to see. But I do think the bisexual piece is interesting because I think people still look at bisexuality as a phase. “Oh, girl, he’s just in the closet. And you know, he’ll be gay, he’ll come out in another five years.” But here you have a guy, [the man who asked the question,] who is sixty years old. And he came up to me afterwards and he was like, I want to thank you again for bringing that to light because people ignore you [if you say you are bisexual]. It’s kind of like the oppressed becoming the oppressor. It always happens. So, I often observe this within sexual orientation things. When gay people feel marginalized from heterosexual society, from straight, normative society, they create this construct of what “gay” is. And when you don’t fit neatly into this construct—whether it be you don’t go to gay pride parades, you don’t wear a rainbow flag, you don’t listen to Cher—you don’t do certain things that they deem as defining as being “gay” socially, then all of a sudden you’re in the closet, you’re self-hating, you’re suffering from internalized homophobia. And where does that leave room for diversity in sexual expression and sexual identity expression?

And some people have even gone as far as to say, well, I’m bisexual when it comes to physicality… I can have sex with anybody and I enjoy it and I’m just as equally attracted to both men and women, but my emotional connection tends to be with a man or with a woman. And I think those kinds of layers and nuances of bisexuality—people should understand it’s not just about the sex – people get different things from different people. We did a study with bisexual men and one of the things that came up a lot was the whole notion of gender role norms and gender performances. And what are men supposed to do when they are in relationships with women? Gender norms tell us that men are supposed to be the strong ones, they are supposed to be the provider, they are supposed to be the one that the woman put’s her head on their shoulder and they say, “Honey, it’s going to be okay.” But who actually does that for the men who want that? Because the woman is going to be like, “Punk-ass bitch. Why are you…? You want to rest your head on my shoulder?” Because women are looking to you for strength, so in that kind of traditional gender role construction, women are weak and passive and men are supposed to be strong. And so many people have bought into that but some guys are like, I want to be held. Or, when I’m hurting I want to be able to cry and I want to put my head on someone’s shoulder. And people don’t give folks the space to do that and not be critiqued. I think that’s why some people do embrace bisexuality because they can get different things from different people, whether it be emotional or physical. Kali, what do you think?

Kali Lindsey: I’m with you. I appreciate the younger generation cause they’re rejecting all of that—all of the identities, because it doesn’t speak to their fluidity. You know I talked about how I come from the psychology school so I’m much more aligned with the Kinsey scale, where it’s all fluid. And most people fall on the spectrum of bisexuality, very few of us are in these hard, rigid identities. But, you know, it’s interesting that they feel so comfortable articulating that in LGBT spaces, but where were a lot of the bisexual advocates when the down-low conversation was happening? Like, they’re being reductive, they’re not acknowledging your presence, “DL” is just a denial of the challenges of living a bisexual lifestyle, and many of you are silent. This is a clear example of stigma and resilience, there is protection that comes with bisexuality. The side that visibilizes opposite-sex interactions and acts as a silencing force for some when the community is criticized. And it is the gay-identified man that is coming out to say, that’s inappropriate, these individuals have relationships and expressions, and then gets villified. But where were the bisexual organizations talking about how reductive the whole down-low conversation was? We were giving deference to African American women who felt harmed by these men in their lives who were betraying them, or so they thought. But no one ever acknowledged that we weren’t respecting different levels of sexual diversity, and that the betrayal was actually on our end for giving voice to the whole “down low” phenomena.

David Malebranche: JL King was around.

Kali Lindsey: Exactly, and Oprah endorsed him. And many of us gay men continue to support Oprah and continue to celebrate her successes and her voice even though she has contributed to pain in our communities with some of the choices she has made. And some of us have even written blogs about it and put it on Facebook and whatnot [laughs]. But it’s unfortunate that sometimes it’s easy for us to go to the oppressed and express our anger and oftentimes we don’t fight against the systems that continue to oppress us. It’s not the oppressed that are doing the bulk of the oppression. And I’ll set aside the transgender conversation because I’m absolutely in agreement with that. But oftentimes we just find it so much easier—and it happens within the black community too—a lot of times black-on-black crime happens because we know that it’s not going to be prosecuted. I’m less likely to kill the white person because I know that law enforcement is actually more likely to investigate that crime. But if I kill a black person, or a black man, I’m more likely to be able to get away with that. So I’m more inclined to act out or do something without thinking it through completely when I know that the consequences are going to be less severe. So we have to go back to the original point, we have to attack the cause and not the symptom. We have to go further upstream.

David Malebranche: I don’t know why this just came to my mind, but somebody got really mad at me one time when I told them—you know they were pushing for this whole gay marriage thing and everyone was like, “gay marriage, gay marriage, gay marriage” and “if you’re not on board with this you’re suffering from internalized homophobia”—and I turned it on them and I said, “Look, you’re calling me the internalized homophobe, but you’re chasing after a social construct that is based after a heterosexual norm, and so, who hates themselves more? You or me? Because if you really loved yourself, you’d create your own definition of what a union or partnership is. And don’t say this is all about romance or this, that, and the other, because it’s not. A lot of this is a business model, so claim that. That you hate yourself for being homosexual so you’re chasing after all of these things that are viewed as normal and straight and heterosexist and this kind of stuff. Yes, I understand the financial benefits, if my partner dies and the house and whatever and I don’t want to get saddled with the taxes, and I want those benefits, but I think that’s where Kali was talking about the rules are fucked up. So, instead of saying we need to be able to marry too, why don’t we fight this paradigm and this structure that says if you’re not married… Why don’t we change that rule? Instead of us running around like chickens with our heads cut off, chasing a social construct that even straight people can’t get right and end up in divorce 50% of the time? They’re not even getting it right, so why am I holding this up as my ideal? Unless I’ve really bought into some heterosexual norm and don’t really like myself for who I am?

John Schneider: Haven’t gay people suffered enough?

David Malebranche: [laughing] Exactly! And that’s what people have said. I heard a straight comedian once say, “Absolutely, I want you [gays and lesbians] to suffer just as much we do. Have marriage. And you can understand what kind of bullshit we go through.” I thought that was funny.

Kali Lindsey: Yeah, and I think it goes to some of the asset-based and the resiliency models that we try to promote. Part of the challenge of bringing forth more of those resiliency models is that we have to appreciate and begin to celebrate how we’re different.

David Malebranche: Absolutely.

Kali Lindsey: And we don’t want to acknowledge and accept it and we want to blend in and be part of the larger system. And unfortunately our uniqueness is what makes us powerful.

Katie Berringer: And I think you brought that up, David, with intersectionality and how we can begin to celebrate the differences.

David Malebranche: Yeah! And the uniqueness is why people have migrated to gay ghettos, to gay enclaves—because you don’t get that in suburbia. And I think one of the things that you said, John, which I’ve always been preaching, so I really appreciated it when you said it was, “Why do we have to have a comparative norm when we do our studies?” People used to always ask me when I did studies—and if you look at most of my research I exclusively interview black men—and people would always ask, “Why aren’t you including whites and Latinos?” And I would say, “Why don’t you ask the people who only study whites and Latinos why they aren’t including black people?” Stop acting like there has to be a reference point and has to be a norm. This research will stand on its own. And within the black community there’s more than enough diversity, there’s more than enough variety that we can get some interesting conclusions and then debunk the myth that there’s just this monolithic mass of people that all act the same way. That doesn’t fly for white people, it doesn’t fly for black people, it doesn’t fly for Asians or Latinos or Native Americans. But I really appreciated when you said that because I’ve been screaming that at the top of my lungs forever. And I’ve actually had grants rejected or had to re-submit them over and over again because they wanted a white norm to compare it to.

John Schneider: Yeah, it infuriates me.

David Malebranche: Yeah, and if someone wants to study just white people, I’m okay with that. I mean the unfortunate reality is that most of the studies that influence medical recommendations, public health recommendations are with white people, so me doing a little qualitative study with 30 black people and not including a white person? Don’t you think that may slightly make up for the unbalance of the past several decades? Give us a break. Let us have one study. We can stand on our own. So, it’s always humorous to me.

Kali Lindsey: It’s like the statement, which one is more impactful, the 18 year old black gay man who has a 60% chance that he’ll be HIV positive by the time he turns 40, or the fact that black gay men are 22 times more likely to have HIV than white gay men? Which one has more impact? Hopefully, people are more concerned with 60%.

David Malebranche: Yeah, I almost don’t care about the comparison. Focus on my likelihood.

John Schneider: Well, David and Kali, thank you both for indulging us. That was really nice.